OUR BLOG

A place to read up on the concepts that are key to our approach to highly effective pedagogy.

How to Foster Collaboration with Multilingual Learners

“Now turn and talk to your partner,” says the teacher to her diverse classroom of multilingual learners after presenting them with a prompt she’d like for them to discuss. “Discuss the different types of indirect characterization that we learned about in yesterday’s class.”

And then, to her dismay, silence.

This is an all-too-common problem that many teachers encounter on a regular basis.

Although the instructional routine of “Turn and Talk” is intended to facilitate discussion and collaboration among students, it often fails to deliver the results that educators hope for.

The reason? The prompt can just as easily be answered silently and individually as together with a partner, an approach that shy, nervous students will almost certainly prefer to actually engaging in discussion in a language that is new for them.

Much of the time, MLL teachers might rely on their own energy reserves to promote discussion, or on the more socially inclined students to get the conversation going. While this approach to fostering collaboration can sometimes get the class going, it is exhausting for the teacher and will have inconsistent outcomes depending on the personalities and demographics of the class.

What is missing from the “Turn and Talk”, like many other instructional routines meant to get students talking to one another, is a reason to collaborate and clear guidance for how that collaboration is supposed to happen. Without these two key ingredients, interactions between students are likely to be stiff, stale, and unproductive in terms of the lesson’s objective.

Research has clearly shown that students benefit tremendously from participating in collaborative classrooms in which they, not the teacher, do the talking. Here are just a few of these benefits:

Exposure to an increased complexity, frequency and variety of language. When students are placed in situations where they need to be agreeing, disagreeing, negotiating, etc. they have the opportunity for a wider variety of functional use of language than in traditional exchanges in which the teacher plays a central role in all exchanges.

More equitable participation from and exposure to diverse voices and perspectives. Students, especially those at more beginning levels of English proficiency, may feel intimidated to speak in front of a whole class, but comfortable speaking with just one or two other classmates. With their ideas validated and strengthened by peers in a small group, many more students feel emboldened to then share with the larger class, thus enabling their voices to be heard.

Greater access through translanguaging (flexible use of home language). Strategically pairing students who speak little to no English with other students who are more fluent in English but also speak their home language provides a powerful scaffold and entry point to classroom activities. For many collaborative activities (brainstorming, negotiating, prioritizing, etc.), students can and should be encouraged to use whatever language or language(s) they wish even if they eventually have to produce something in English to share with the larger class or to communicate their understanding to the teacher.

Increased student engagement. Our general guideline when coaching teachers is that if they are speaking for longer than three-minute stretches at a time, they will most likely lose the majority of MLLs at beginning English proficiency levels in their class. Studies have shown that greater engagement in a collaborative classroom also leads to greater retention of material.

Improved interpersonal skills. By explicitly teaching interpersonal skills to students and then providing them countless opportunities to practice applying them, teachers better prepare their students for the 21st century workforce.

So if collaborative support is lacking in classrooms, students stand to lose quite a bit from the quality of their educational experiences. All teachers of MLLS should strive to incorporate these measures into their lessons. The problem is that most teachers do not know how to do so.

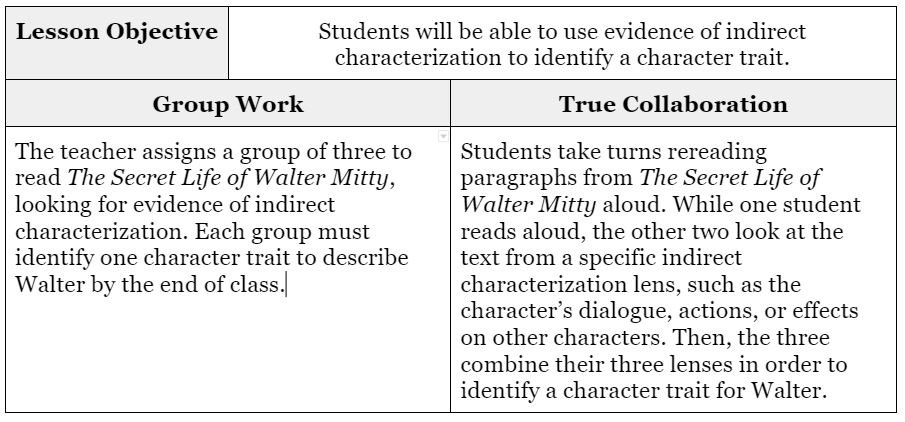

One of the main issues that complicates this is that many teachers might confuse the concept of “group work” for true collaboration. In group work, the teacher may simply assign students into groups to work on the problem or project at hand, without much guidance in terms of who takes on what role, or how to communicate ideas to one another. But this is different from true collaboration, in which the teacher has strategically structured the activity such that students must rely on one another in order to complete the activity.

To get a better sense of the difference between group work and true collaboration, let's imagine an ELA class in which the teacher wants students to look for evidence of indirect characterization in order to identify a character trait for the protagonist. Take a look at how group work might be organized versus true collaboration:

As you can see, collaboration in the group work version of this assignment is more of a suggestion, but students might be unclear as to what role they are to play. Perhaps there might be a Type A student who takes the initiative to do so, but that is certainly not guaranteed. By contrast, in true collaboration, each student has a specific role through which to view the text, and all roles are required in coming to a consensus about the best answer to the prompt.

One of the main differences between group work and true collaboration is the use of micro-structuring, the process of providing more structure to an activity. The structure can be added in several ways, listed below:

Grouping students according to the number of meaningful roles within a task, as the example on indirect characterization demonstrates.

Using an activity structure with protocol, such as Think, Pair, Share.

Promoting structure independence from the teacher through the use of a graphic organizer that is designed to facilitate the activity from start to finish.

While this blog has provided you with some ideas for the initial steps in implementing truly collaborative activities in your classroom, the real “Square One” for embarking on this journey begins in your own mind.

Transforming more teacher-centered activities within a lesson plan to those that are more student-centered requires more than just a rethinking of the activities themselves; it requires a shift in mindset about the nature of learning.

Part of this mindset is the belief that students will benefit more from learning from each other instead of just from you, since they will be required to actively construct knowledge through brainstorming, debating, and negotiating with one another instead of passively taking notes on the new knowledge that you have shared with them.

Another aspect of this mindset involves ceding control (this can be hard for teachers!) in a different way: the need to know exactly what all students are talking about at all times.

Yes, it is possible that students at times will veer off task and you won’t always know it the second it happens, especially if they are speaking in their home language instead of English.

We would posit that you also don’t know when their minds wander off task as they lose interest when teacher talk goes on too long.

A collaborative classroom is of course louder than an orderly teacher-centered one, so tolerance of noise is important. This goes back to having the mindset that collaboration is important for productive learning so more noise is an easy trade-off to make.

The truth is that a lively, collaborative classroom is one in which learning is happening at a much faster rate with more efficacy in terms of student outcomes.

How to Foster True Collaboration in YOUR Classroom

Are you ready to learn more about the design of true collaboration, such that your MLLs are provided with everything they need to be successful? Then check out our upcoming event on October 27th, Fostering Collaboration for Multilingual Learners.

In this workshop, you will learn more about the differences between group work and true collaboration, understand key components of micro-structuring activities, and then identify opportunities to add true collaboration into lesson plans.

Finally, the facilitator will share resources with you that allow the implementation of new learning into your classroom TODAY., resources that you will be able to use again and again throughout your teaching career.

What students do when they first enter the classroom matters. Here's why.

Homeostasis: Noun. the tendency toward a relatively stable equilibrium between interdependent elements, especially as maintained by physiological processes.

Got it? Good, because now I’d like you to compare and contrast how homeostasis works in your own body to how it works in plants. And no, you can’t use Google.

If you’re feeling a bit upset over the unfairness of the task outlined above, you’re certainly not being unreasonable. There are several important aspects of pedagogy missing from it, one of which is that you were not given the opportunity to activate your prior knowledge on the concept of homeostasis before diving headlong into its complications.

Activating prior knowledge is the first important step in teaching a new concept to students, and yet it is often overlooked.

Essentially, it is uncovering what students already know about a topic in order to find a familiar entry point from which to build upon. It is the first step in building the schema upon which all the lessons to follow will depend. Without it, your students may struggle to attach meaning to the new words, phrases, and concepts that are crucial to content mastery.

One of the best ways to activate prior knowledge is through the use of a “Do Now”, a warm up activity or task that students engage in immediately upon entering the classroom.

Do Nows can serve a variety of purposes. They can be used to review older material, discuss answers to a quiz, or to just get students settled into their seats and ready for the day’s lesson.

However, Do Nows are especially useful in activating prior knowledge because of their position at the very beginning of a lesson. They can be used to bring that vital concept mapping front and center into the students’ minds, such that they are now more open and ready to receive new information.

An example of a prior knowledge-activating Do Now is a semantic web, such as the one that you see below:

A semantic web, also known as a semantic map, is an excellent way to afford students the opportunity to bring their prior knowledge on a given topic into focus, priming them for your lesson.

So let's return to that task at the beginning of this article.

Instead of just defining the term “homeostasis” for students and then demanding a complex activity, what if we first ask them to develop a semantic web around the key concept of equality.

In the center of the web, students would write the word “equal” or “equality”.

Then, they would fill the bubbles around this word with symbols, words, pictures, phrases, events, people, etc. that they were already familiar with and that they associate with equality.

If you were a student, you’d realize that you already know quite a lot about this important concept before you ever engaged in rigorous academic tasks. This would build your confidence to explore, thus lowering your stress level and making your more open to receive additional information.

Let’s take a look at all the benefits.

First of all, this activity would make the key concept of homeostasis, the maintenance of equality, accessible to all students in that they would be generating all these associations on their own, unaided by academic articles or rigorous, stressful tasks.

Second, a semantic web would build schema around the concept. This means that students are constructing a framework for organizing and receiving new information. Later in the learning process, when the rigor increases, this framework can serve them well, as they build connections to the web.

Third, this activity is concise. It takes place at the beginning of class and is directly related to the concept that you want them to master.

Lastly, a semantic web sparks thinking. Though students may not realize it because they’re just drawing on their own personal experience, they are engaging in higher order thinking. Their synapses are firing, they’re making connections.

Activating Prior Knowledge is as easy as learning the ABC’s

If we put the four characteristics outlined above together we’ve essentially got a very easy system for remembering how Do Nows can be utilized to activate prior knowledge:

A is for accessibility

B is for building schema

C is for concise

S is for sparks thinking

While listing these characteristics in this way may seem like a strange acrostic poem, it is a great way to remember the vital components common in all quality Do Now activities.

As it turns out, a semantic web is just one among many that can be used to this end.

Agree/Disagree, structured conversations, and card sorts are other examples that you can use to activate prior knowledge in your students, and thus give them a strong base from which to explore complex topics.

Once you’ve got this down, the next step would be to expand upon what students already know by building background knowledge.

Activating Prior Knowledge for YOUR Students

Do you want to learn more about how to use Do Nows to activate prior knowledge of your students in your content area?

We currently offer a specialized professional development course that is guaranteed to make you a Do Now expert, thus maximizing student achievement in the classroom.

To learn more about this unique professional development experience, go to our Services page and click on our Making Complexity Accessible to Multi-lingual Learners workshop. This workshop is offered both online and in person.

Not All Graphic Organizers Equitably Help Students Achieve Academic Goals. Here's Why They Need to Be Rethought.

The graphic organizer has been a cornerstone of pedagogy for a long time. I think we can all remember a time when we were students in school and told to brainstorm ideas using a “mind map”, an interconnected web of bubbles and lines, or to compare two things using a Venn diagram. This pedagogical tool has been in use for decades, and for good reason. They’ve been shown time and again that they facilitate students in a variety of higher order thinking skills, including multi-lingual learners and students with IEPs.

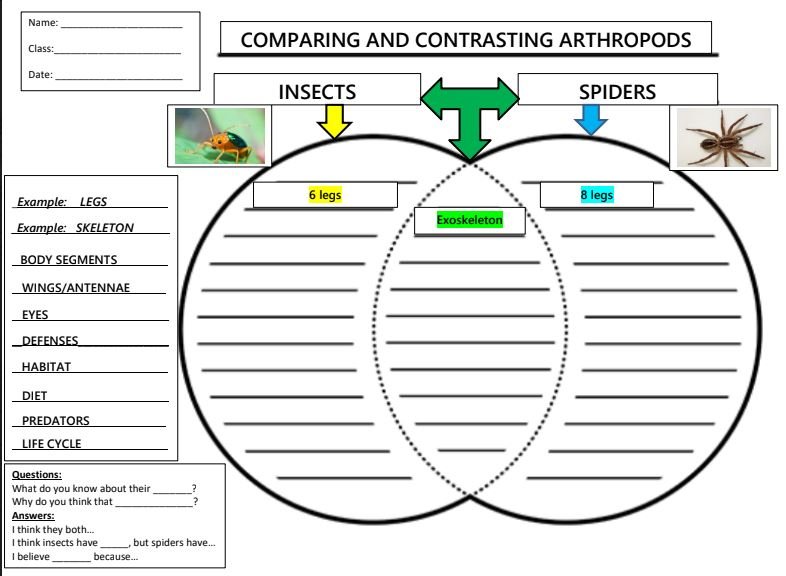

However, not all graphic organizers are created equal. While their use in the classroom may provide a general scaffolding, not all students will be able to engage with them on the same level. For instance, let's examine the Venn Diagram, the classic way to get students to compare and contrast two things. Take a look at a typical template for this graphic organizer below:

A typical Venn diagram template

At first glance, everything seems to be ready to facilitate student engagement. There are spaces at the top for students to identify the two items they are supposed to compare. There are two places on either side for students to list differences and one in the center for similarities. And there are lines indicating where students are to write their thoughts. Everything is in its right place.

Now let's imagine passing this graphic organizer out to a modern day classroom, full of students from different cultural, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds. Many of these students will be Multilingual Learners. And within this demographic there will be many different home cultures and first languages: Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Haitian Creole, Urdu, French, and Vietnamese to name a few.

Then you consider that there are a host of other variables impacting a student’s ability to interact with the standard Venn diagram template. Not only do students have different cultural and linguistic backgrounds, but also different levels of literacy in those first languages. Some students may have strong literacy in their first language, while others may be weak. Given that research has demonstrated that phonological awareness in a student’s first language predicts successful literacy acquisition in their second language, the needs of students will differ.

There is also the variable introduced by Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE), who may be seeing a Venn diagram for the first time in their lives. By contrast, there may be students who are well-versed in its use, having used it dozens of times before.

Inevitably, all these variables will guarantee that students achieve varying levels of success with the standard Venn Diagram graphic organizer, and in varying amounts of time. If the teacher simply hands out the graphic organizer as is and delivers some oral instructions, here are some outcomes that one can expect;

Some students will completely fill out every line of the Diagram, while others will barely write a single sentence.

Some students will believe that they have finished the graphic organizer in 5 minutes or less. Others will not even be half-way done even when class ends forty minutes later.

Some students will have compared and contrasted physical characteristics, while others will have written about abstract concepts that require more thought and analysis.

Some students will have precise, detailed, and entirely correct information on their graphic organizer. Others will have mostly incorrect information. Most will probably have a mix of correct and incorrect information.

There are a few ways that a teacher can try to remedy these problems. A common one is to have students compare their graphic organizers to each other towards the end of the class, so that students have an opportunity to check their work against their peers.

While this is a form of collaboration, it really just allows loopholes for students to bypass higher order thinking on their own and rely on others. If a student is not confident in their work, they may just copy their partner’s responses word for word, an act that requires no higher order thinking whatsoever.

So what's wrong here?

Rather than try to fix problems of unequal student outcomes after students have already completed their work, wouldn’t it be better to prevent them altogether? In order to do this, we need to understand what the Venn diagram itself is lacking.

First of all, there is no chunking in the basic Venn diagram template. Chunking is essentially breaking a task down into smaller parts. Whatever students are comparing, they will be studying something in which that information lies, whether it be a picture, a text, or video. However, if that medium is not chunked into smaller bits, it is incredibly easy for a student to become overwhelmed, which raises their stress level, which in turn decreases their ability to successfully engage in the task at hand.

Second, there are no visual reminders of what students are supposed to look for in their comparison. Studies have shown that the use of visual aids can help students to absorb the content and become more interactive with their peers because there is far less fear of giving wrong answers. If visual aides were on the page, students could refer to them for a language-free scaffold that reassures them of what they’re supposed to look for.

Third, there are no clear expectations for the quality of work that the teacher is expecting of students. Should students write full sentences or just words and phrases? Should students get 3 differences and 3 similarities, or is the number of details not important? Should students look for superficial differences and similarities, like physical descriptions, or look for more abstract ones related to a theme? It’s not clear, and this lack of clarity is one of the reasons why students will produce a range of work quality.

The fourth problem is related to the third. There are no clear directions. When students find themselves confused, they cannot seek an answer themselves. They will have to rely entirely on the teacher for clarification. This may not seem like a problem for, after all, that is one of the roles of a teacher. But when you consider all the clarifying questions that may arise in a class of 30 students, it is likely that the teacher will be overwhelmed. Another issue with the lack of direction on the page is that not all students have the level of confidence to approach the teacher in the first place. A shy or insecure student may feel bad that they need additional support, and just say nothing at all.

A fifth issue is the lack of writing frames. Given that students will be approaching this task with a huge variety of linguistic backgrounds and abilities, many will need support in how to express their understanding. A student may have identified a difference between, say, insects and spiders, but may not have the knowledge of the English language needed to communicate that on the page. The result will be that the student either writes nothing or writes something that the teacher has trouble understanding, both of which are inaccurate representations of what the student actually knows.

All of these issues combine to create some formidable obstacles for Multi-lingual Learners in mastering the content and skill objective. If they aren’t resolved on the page of the graphic organizer, the teacher will almost certainly encounter a host of issues in the classroom.

So what does a Venn Diagram that has addressed these issues look like? Take a look at a modified version below:

In this Venn Diagram, you can see these five issues have been resolved.

First, the Venn Diagram is appropriately labeled and chunked into sections. In addition, categories of comparison have been provided so that students can focus their thinking on one thing at a time.

Second, there are visual aids that remind students not only of what they are comparing, but also a color coding system to indicate what qualifies as a difference and as a similarity (blue and yellow indicate differences while their combination, green, indicates a similarity).

Third, the expectation of the teacher is clearly demonstrated by the use of examples for each of the categories.

Fourth, the directions are on the page, not only denoted by the label of the Venn Diagram, Comparing Insects and Spiders, but also by the categories of comparison on the left hand side, which indicate how that comparison is to take place.

Lastly, there are language frames which allow Multilingual Learners to structure their written work and their feedback to the partners. This fosters collaboration, allowing a more equitable way for students to check their work against that of their peers and resolve misconceptions.

So, now compare the first Venn Diagram with the second. If you were a Multilingual Learner, which one would you rather receive from your teacher?

To sum up, the criteria of chunking, visual aids, clear expectations, clear directions, and language frames are absolutely essential in producing graphic organizers that create a more equitable classroom in which Multilingual Learners can thrive. Modifying your own graphic organizers to make sure they meet these criteria is a sure way to boost student achievement.

How to Create Amazing Graphic Organizers in YOUR Classroom

The Venn Diagram is just one of many types of graphic organizers that students need to navigate in the classroom. Flowcharts, mind maps, timelines, storyboards, cause/effect chains, KWLs, concept maps, and many others abound.

Do you want to learn more about how to construct these graphic organizers in a way that ensures the success of your Multilingual Learners? Check out our free resource on the Criteria for Effective Graphic Organizers or enroll in the specialized workshop that we offer on this important topic.

The Importance of Building Schema

MLLs, and all learners really, need to build schema in order to comprehend the new information that is presented in texts and certainly before the teacher asks them to do anything requiring higher order thinking skills.

So how can a teacher build schema for their students?

Here’s some great advice: To free up your crew, store the spinnaker in the leeward pouch so the helmsman can hoist it alone. When the helmsman does hoist, you should bear away to a run or broad reach.

Now please do the following tasks with this advice:

Explain what it means in your own words.

Evaluate the quality of the advice. Is it worth following? Why or why not?

You have 5 minutes to complete both tasks and cannot use any outside resources to help you.

What's that you say? You think this is unfair? C’mon, you’re only working with two sentences! How hard can it be!?

I’m joking of course. Unless you are an experienced sailor, you would almost certainly be unable to do either of those tasks.

The reason is that you do not yet have the frame of reference in which to situate and make sense of the complex ideas in that advice.

This frame of reference is known as schema, and it is essential in the process of learning new information.

In the above example, your lack of schema is what prevents you from being able to do the two tasks asked of you: Explain the meaning of the text and then evaluate it.

You have nothing familiar to compare the new information to, and therefore can’t make heads or tails of it, much less do anything with it that requires higher order thinking.

You might struggle to think of an example wherein such unfair tasks are assigned, but the reality is that many students encounter exactly this type of situation in their classroom on a daily basis.

These unfortunate experiences are especially common among multilingual learners (MLLs), who are not only struggling to understand the deeper meaning of the content, but also trying to navigate linguistic and cultural differences between their home lives and their school lives.

MLLs, and all learners really, need to build schema in order to comprehend the new information that is presented in texts, and certainly before the teacher asks them to do anything requiring higher order thinking skills.

So how can a teacher build schema for her students?

Step One: Activate Prior Knowledge

The first step is to activate the prior knowledge that students already have. This gives students an entry point into the content of the lesson.

For example, in the above scenario, the average reader doesn’t have the knowledge of sailing needed to understand the advice being given. So she needs an entry point, something to bridge what they already know to the new and unfamiliar topic of technical sailing.

But what is something that anyone would have direct knowledge of, regardless of their cultural or linguistic background?

The wind.

A familiar concept, wind is not something that you need to read about. It is already known to you through direct experience.

So let's say that instead of first giving you the piece of sailing advice and asking you to complete academic tasks based on it, I just gave you a paper airplane.

I could then ask you to throw this airplane towards an electric fan at various angles, noting how the wind altered the path of the plane.

In this activity, you wouldn’t need much language to understand the basic concepts of aerodynamic lift that are essential to knowing sailing techniques.

In a way, you already know them, and are using this knowledge in your play with the airplane.

Step Two: Connect Prior Knowledge to Complex Topics

Fully confident in your understanding of wind, you would now be ready for a bridge to the new, unfamiliar concepts of sailing necessary for understanding the technique advice.

Step two is to build that bridge, to make that connection between the known and unknown.

To do this, I would visually replace the paper airplane with a sailboat, and ask you to make predictions about how this sailboat might behave as it approached the wind from different angles. I could even ask you to give advice to a hypothetical sailor on what he should and should not do in order to reach a certain destination.

Though you lack the nuanced technical vocabulary of sailing, you could do this through activating what you already know about wind and how it affects objects that use it to move.

With your prior knowledge now activated and connected to the topic at hand, at this point you’d be ready to receive some of the technical vocabulary needed to understand and evaluate the sailing advice. “Bear away”, “run”, and “broad reach” are all terms that merely describe the sail’s position relative to the wind direction. In essence, they’re just fancy names for things that you already know about through your experimentation with the paper airplane.

After a brief vocabulary introduction, you’d be fully prepared to tackle those two original tasks with little difficulty.

Building Schema in YOUR Classroom

The above example highlights why it's so important for teachers in all content areas to build schema before diving into the complex topics of their subject. Establishing that framework ensures a more equitable access to the learning experience, regardless of your students’ cultural or linguistic background.

This makes building schema a powerful tool in closing the achievement gap, especially among Multilingual Learners (MLLs).

When thinking about building schema in your classroom, here are some questions that you should ask yourself:

What do students already know about the topic?

What activity would connect the central concept and/or target content to something already familiar to students?

What additional background knowledge will support them in building schema around the central concept/target content?

What activity would bridge from the activating prior knowledge activity to the target content?

Asking yourself these questions can help guide you in the creation of high-quality schema building activities that are sure to benefit your students’ ability to engage in your rigorous content.

Next Steps:

Do you want to learn more about how to build schema in your content area through activating and connecting the prior knowledge of your students?

We currently offer a specialized professional development workshop that is guaranteed to make you an expert on building schema in your classroom, thus maximizing the learning experience of your students.

Go to the Services Page and click on the Building Schema workshop to learn more about this unique professional development experience.